Tia Stenson is a guest blogger for Permanent. Tia is an emerging archivist and a recent graduate from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, with a Masters in Library and Information Science, and a concentration in archival studies.

Picture this: you came into possession of a relative’s documents, photographs, and scrapbooks. Now what? What do you do with it besides put it in a box and place it in the attic to be forgotten about (please don’t do that)? Well, I am here to help.

My name is Tia Stenson. I am here to help you. I am going to share the best practices I have learned at school, and my various internships, so you can best care for your own collections.

Preparing to Digitize

Let’s jump into digitization! Or we don’t. There is a reason that most archives and museums do not have all their collections digitized and online. There are steps that they have to take before they can digitize their materials. Archivists need to know what they have so they can most effectively share those resources with you, their patrons. This process includes creating lists of the materials in the collections, ensuring the privacy of their donors is protected, and labeling the materials to be findable on their catalog or an internet search.

Most archivists state that the most important part of their digitization project “is the value of having a collection thoroughly processed and rehoused” ahead of time. For you this means knowing what you have by creating an inventory, or Finding Aid, of your collections.

This is an essential step in the path of digitizing your materials and making them findable to your family and friends by keeping them organized.

Surveying and Arranging

When archives receive new collections, the collection goes through a system called arrangement and description.

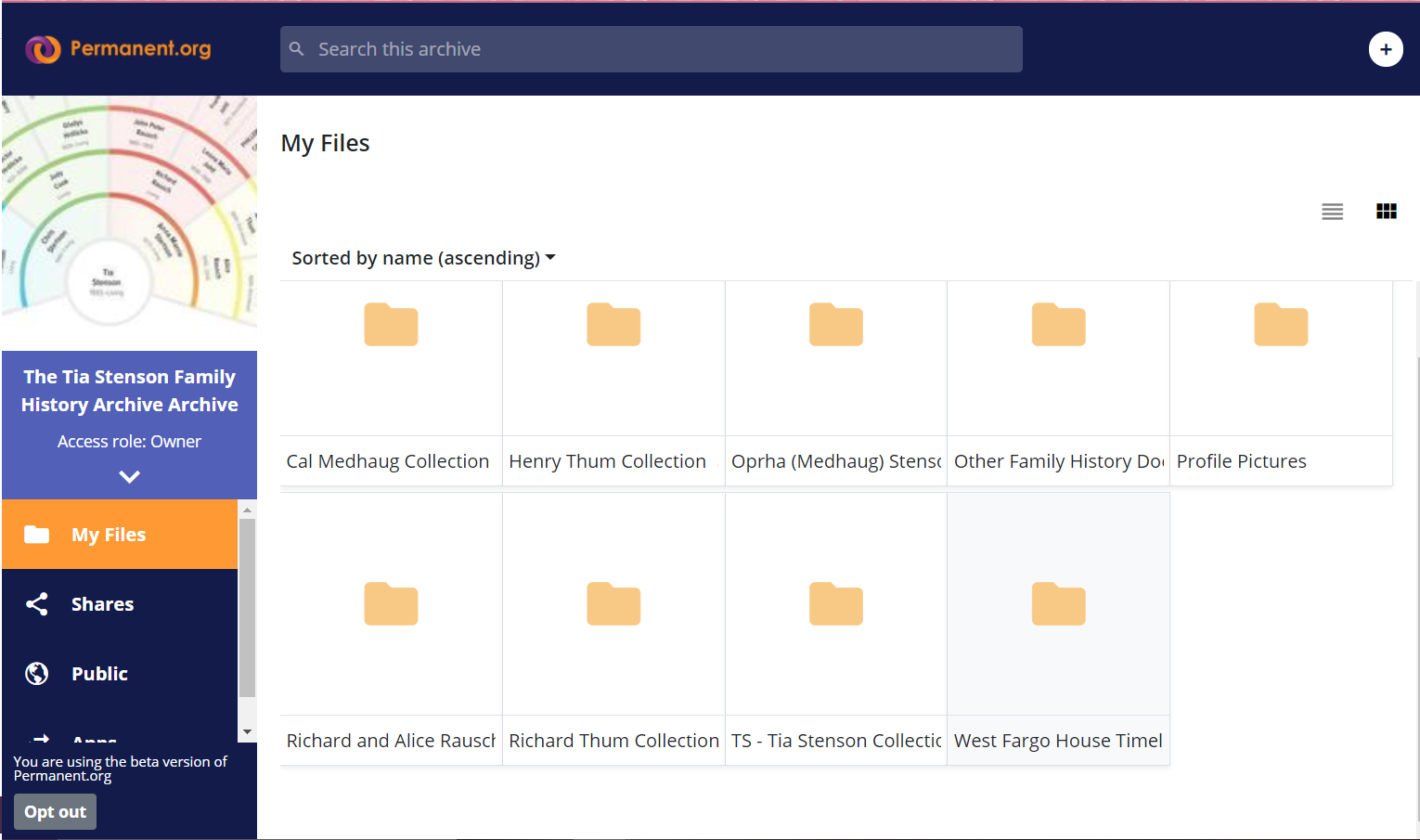

The arrangement is basically organizing your collection. This means physically placing your collections in a logical order. There are two principles that archivists work with, respect des fonds and original order. Basically, respect des fonds means materials related to the same thing, or created by the same person should stick together. For example, I have various collections of materials that remain separate, such as my own personal collections, my Rausch grandparents, my Great Uncle, Richard Rausch’s materials, and my great-grandmother Orpha’s collection of materials.

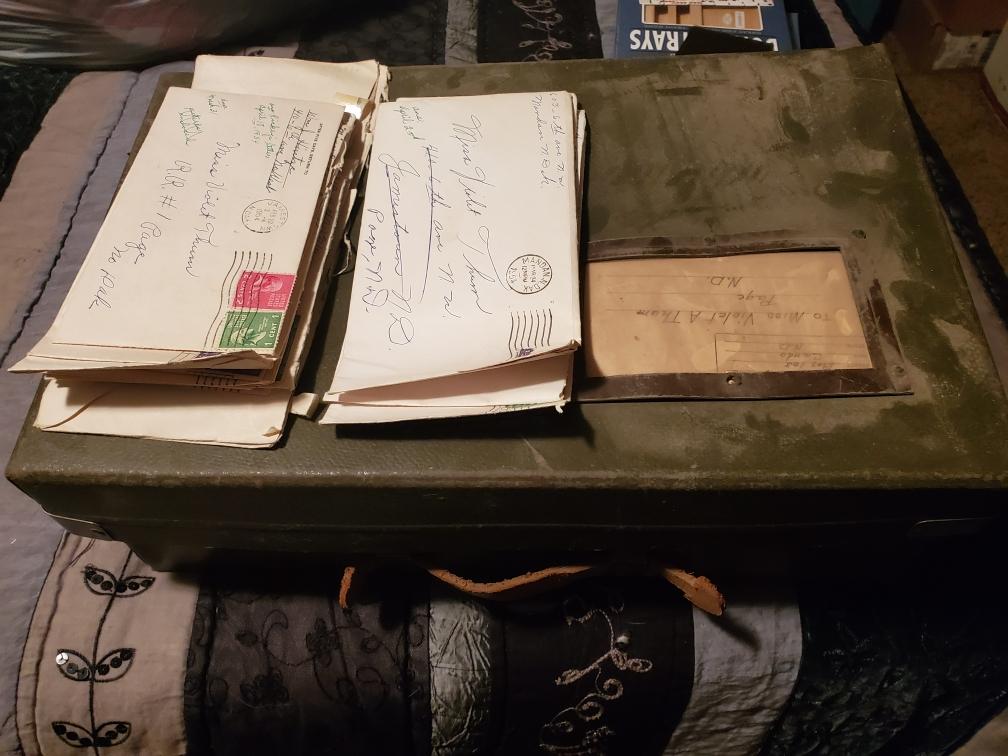

Original order means keeping materials in the order that they were found. However, this might not always be attainable if the materials are found with no discernible order in a box. I will be using the example of the most recent collection that has come into my possession, the Richard Thum Collection. My great uncle passed away last year and he lived in the family farmhouse. After his death, when my parents went through his home, they found a treasure trove of family history documents on himself, his siblings, and his parents, and documents related to the farm. These were housed in various boxes and had no particular arrangement. I had to organize them myself.

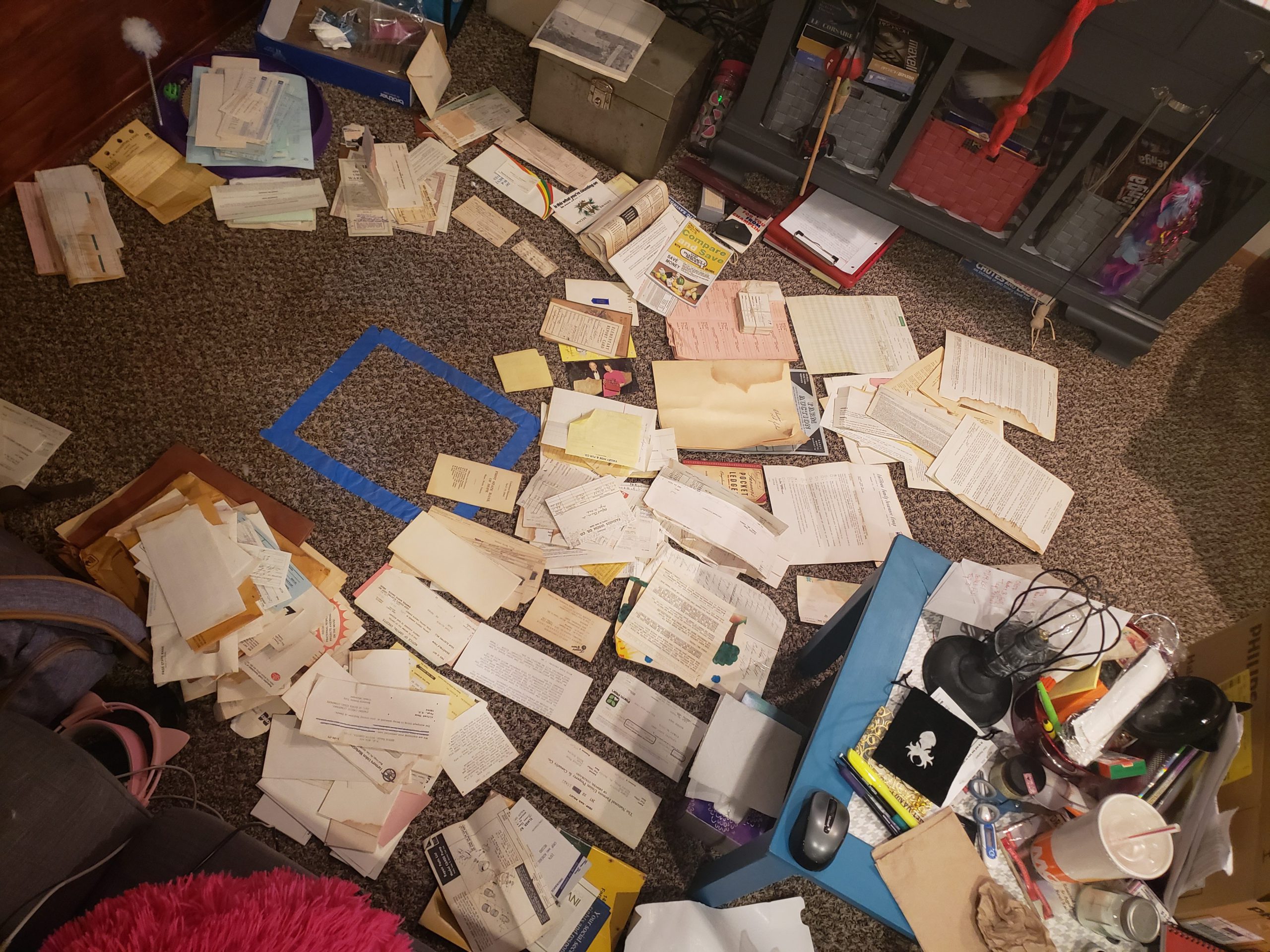

To begin, I did a general sorting of materials putting like materials together, such as family letters, medical documents, and farm documents. I recommend giving yourself room depending on how many documents you have and refrain from having food or drink close to these materials as you don’t want an accidental spill. After the initial sort, I put them into folders and generally label the folders with a pencil.

Then I sort and organize again. I take a single folder and re-sort the materials inside of it. This often means separating the documents out by year, but it also could be separating out more specific documents that are the same type, such as contracts, deeds, or report cards. Each of these new separations needs its own folder. These folders should be labeled as specific as possible. The label should tell a person what type of document is inside, who or what is related to the documents, and in what year the documents in the folder were created. If the year is unknown, just state “undated”. An example of a proper folder title would be, “Henry Thum Algebra Homework, 1954”. At this time I also remove staples, paper clips, and rubber bands. Staples and paper clips rust and cause damage to paper, rubber bands dry out and do the same. If you want to keep a multipage document together use plastic paper clips.

The final step of arrangement is putting all the folders you created in a logical order in a box. For my Richard Thum Collection, I grouped folders into a series, starting with Education Papers, Family Correspondence, Financial Documents, Insurance Papers, Legal Papers, Medical Documents, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Miscellaneous Documents (only use this final type of series as a last resort). Some of these series are broken down into smaller sub-series and are placed in a box alphabetically or chronologically. Typically for a series order, you want to put the most “used” series in the front and the “least” used in the back. But it can be organized in any way that makes sense to you and your collection.

Now it’s your turn. Gather all your family history documents, organize them, put them in folders, label them, and arrange the folders in a way that best represents your collection.

Come back for my next post where we will work on describing our collections, so when they are digitized and uploaded to Permanent.org, all that information can be permanently preserved.